Edited by Jadene Mayla

Rob Hopkins is a co-founder of Transition, a community organization dedicated to increasing cohesion between the forces of nature and those of humankind. In his latest book, Mr. Hopkins focuses on resolving our manufactured ills through one of our most valuable resources, our imagination. The book’s title is apt. Instead of confronting the hard and harmful complexities before us - the what is – he offers us the opportunity to consider alternatives – the what if – which embrace creativity, novelty, and a greater participation of human community in imagining the world.

There is also value to the word imagination. It is simple, clear, and everyone understands and uses it; the author uses the word as a new way of speaking about problems. Concentrating and using imaginative power is not as simple a task as might appear, though, according to Hopkins.

Over the years, and due to ever-increasing demands made for our time and attention, the capacity to imagine has decreased in the human population. Before they are placed in schools, very young children utilize their imaginations as a matter of course. It's an innate after all. Every instance of play, or of doing, is an opportunity to exercise that capacity. In one study, according to Hopkins’ investigations, three year olds and younger were given different numbers of toys to play with. The researchers observed that many toys reduced the possibilities and styles of play among the youngsters, while a lesser number of toys increased innovation and creative play. Too many choices produced confusion among the tots. In fact, in another study, little ones were invited into a room with no toys, and soon enough playing with sofa cushions became the order of the day for their amusement.

Imagination, inbred as it may be and disposed by its very nature to expand thinking, is reduced in its influence by the media-rich, ever-more programmed world. The child is enrolled in school. Classrooms burdened with too many students do't allow for free individual expression. Antiquated teaching methods and even lesson content, which many of our grandparents were taught, do very little to extend or nourish individual imagination. Many would say it causes further atrophe. Even in “creative” activities we see this, where adding to one’s list of accomplishments towards a job resume becomes the purpose.

To contrast this disparity in education, the author mentions a popular concept in Japan called ikigai. It is an ideal in living a life wherein loving, and doing, personal capabilities, and making a living combine to create the right balance for each individual.

Such a state might be cultivated in innovative educational systems in countries like the United States. An institute of learning built around this ideology might not be called a school, for it would lay aside the programmed standard curriculum of our current education system. Each student could retain the right to author his or her own education based on interest and aptitude. Such a school was set up by concerned parents in Reggio Emilia, Italy, after World War II. This school is still operating and has a 'maker center' where students utilize creative facilities and guidance to make whatever they need to realize their ideas. Projects aided by qualified guides are the core of studies, and outdoor open spaces are readily available throughout the city’s three dozen schools and toddler centers. This Reggio Emilia model is understandably popular among visitors from abroad interested in innovative education.

Hopkins also notes that for all ages taking the time to reflect, slow the thinking process, and allow for play and straying off task enhances health benefits, especially among those who suffer under stressful conditions.

In another example from the book, a Dundee, Scotland, psychiatric therapy system has been in development since 1997. Initiated by a theatre company wishing to help those with mental disorders, the founders incorporated arts into their program. Those who had been treated at Liff, the city’s psychiatric hospital, exhibited their works of art at a city gallery. Fifteen thousand people attended, and a few years later, the enterprise received funding from the National Health Service. In the process of researching his book, Hopkins visited the site and was invited to attend a day’s activities. Unlike typical psychiatric wards where individual time, space and care are at a premium, once among the attendees he saw how each was treated with warmth and personal care to create something tangible and meaningful. He and his peers were not called patients or clients, they were artists. Those guiding them had personal experience with mental illness and so could bring their insight and compassion to their teaching. When he asked the director how exactly art helped people, her response was (abbreviated):

Art is a form of communication, a social activity, a challenge (which stimulates creativity). It is educational, therapeutic, collaborative (ideas bounce around), can be shared with the community, and meaningful in reducing isolation and improving life. Moreover, anyone can do it.

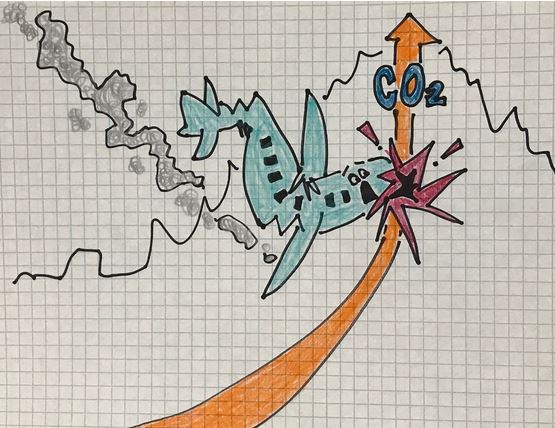

At a time when creative solutions are needed, perhaps more than ever before in the world, a tendency toward conformity as the means for settling issues could be replaced with creative use of our imaginations. Tapping into our creative powers takes focus in a landscape of distractions. Not only do many of us have the demands posed by our children, work, and societal issues, but we are also bombarded by a seemingly endless barrage of information overwhelming our senses.

Value-based labels given to most accomplishments, foisted upon us by society, industry, and an economic system, are given, proclaimed, and pronounced to us and for us. Where is our valuation of the things we do? We must become not only aware of using and pairing our inherent gifts of imagination and creativity, but also of how to most effectively employ that capacity. In South London, members at Transition Town Tooting looked at their area of the city and noticed what they had been unaware of when buses moved along an unremarkable circular street. They asked what if… what if we had a village green right here where the buses make their turns? One question led to another, and before long, some funds were found, ukuleles (plus assorted instruments for others to join) were procured, large pots of flowers appeared, rolls of grass were laid out on the asphalt, and an agreement was arranged with the bus company to make their turns further down the busy High Street for the day. On the day of the “village green” many children came to play on the grass and people from the city joined Transitioners in comradery and celebration of what Transition organizers had done.

Such a transformation is not impossible when viewed through imaginative eyes. It was accomplished because a group of interested people decided what they wanted and didn't simply accept what someone else had been able to envision. They asked what if questions that stimulated others to ask their own. For a fuller account of the event, go to the author’s website: www.robhopkins.net/2017/07/17

Many other examples point to applying what if questions to situations that seem unresolvable. Questions such as what if we made London a National Park? From this comes questions such as What if we could swim in all London’s canals? What if birdsong drowned out traffic noise? What if we rewilded all of London’s golf courses? What if every street had public art? What if we could grow what we need to eat right here where we live? Such questioning can be applied anywhere, and should be.

We can practice honing our imaginative skills with what if questions of our own. For example, here in Pasadena, what if we had a Maker Center where people could come in and make or repair things anytime? What if we had a group of Transition folks who connected requests from crafts people and the folks needing their skills? And what if payment could be cash, commodity or skill trade, or nothing at all?

Such questions generate solutions that are totally dependent on the people involved, rather than requiring outside resources or support. After reading this book, I would like to encourage you to think of your own, and let’s put out what ifs together.