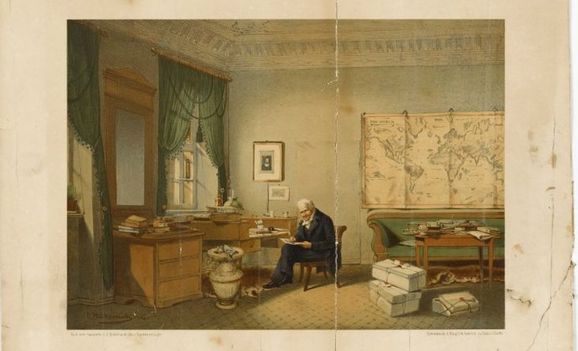

"Alexander von Humboldt in his Study" (Alexander Duncker, Bardtenschlager, Eduard Hildebrandt; 1845; National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Herschel Collection)

"Alexander von Humboldt in his Study" (Alexander Duncker, Bardtenschlager, Eduard Hildebrandt; 1845; National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Herschel Collection) Like many scientists, Humboldt (1769-1859), was unendingly curious about everything related to science. But the German was no mere collector of things scientific. He viewed the world — and nature — as one, as a whole with every tangible and non-tangible entity inextricably related. His “collecting” was an ongoing and earnest enterprise wherein he gathered evidence from every resource he could to make his point.

At the turn of the 1800s, the U.S. had purchased from France the Louisiana territory. President Thomas Jefferson and his Secretary of State, James Madison, were eager to learn what they could about the newly opened prospects to the south. No studies were available, however, until Alexander Humboldt, after exploring sections of South America and Cuba — his first major scientific journey — shifted his return to Europe and stopped in America to meet with the third American President. The executives were astounded by the wealth of Humboldt’s information and perhaps, too, by the explorer’s accustomed rapid-fire delivery in accented English, German and Spanish. In return, they provided whatever information Alexander Humboldt wanted about this interesting and relatively new country.

“Cosmos,” a many-volume compilation that extensively demonstrates the oneness of earth’s interrelated systems, was 20 years in the making and is his most popular work. Humboldt’s favorite, however, was “Views of Nature” in which he poetically describes landscapes accompanied by scientific information. Many of his works were unauthorized and published in so many different sets and volumes, the author himself did not know which ones were published and in what language.

Ms. Wulf said what was needed in her title, “The Invention of Nature.” Heretofore, I had sensed nature all around us, like we all do, marveling at the unbounded green and floral beauty, the sunshine and rainfall, coral reefs and multitudes of living things dependent on them. Still, interrelatedness everywhere was not forefront, not proclaimed. I didn’t fully grasp the depth of nature’s intimate interdependence.

Alexander von Humboldt understood this oneness as an underlying principle of all things (von is the German equivalent of the English Sir; a title bestowed upon honored citizens). Not only was he one of the first to call attention to the destruction man is directing toward Nature, but he is creating a fresh and invigorating view that gives me pause to admire and take in and be grateful. I understand nature today largely because of writers like Andrea Wulf and her New York Times bestseller (it was one of the 10 best books of 2015), and of course Humboldt, who is now more to me than a beneficial cold current welling up off the coast of South America or the name of a CA county.

—Greg Marquez